Monet / Cy Twombly / Joan Mitchell / Patrick Heron

Rationale: This essay is responding to the way painting, especially abstraction, is being pumeled to death with the overloading of our senses with paintings of the ironic/Pop Art/icon style. My frustration is that these paintings are little more than paintings copied from photographs and filled in like a colour by numbers template . My concern is that any aesthetic consideration, when viewing paintings that are abstract in nature, is being starved of oxygen. These paintings require more than an intellectual response of a few seconds, they requires 'time', to reflect, to absorb and to respond...

'A single line, violent, passionate, broken, or beautifully calm, regular, uniform, conveys what we are feeling. It corresponds to what we are living through..' Hans Hartung

Painting. What is it about the act of painting that is so captivating? The process of painting, the creative act of placing pigment on canvas is an extraordinary experience..

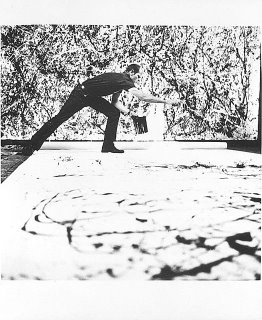

I am thinking beyond any romantic ideas about the smell of linseed oil or turpentine in the studio or the image of the artist out on some kind of action-painting bender; drunk on the stuff in a Pollock-like fury.

Hans Namuth, Jackson Pollock in his studio

I am interested in paintings and not pictures. Paintings that require some thought beyond a merely visual reading of the subject matter. Perhaps, I am thinking about the 'letting go', that is required from us as a ‘viewer’ to go beyond just looking. For me painting and especially abstraction, is an activity that coalesces the engagement between thought, material and action. A process that responds to the 'feel' of the painting.

There is something of the epic, of Renaissance heroicism, in the large painterly canvases of Pollock, De Kooning, Rothko and Kline. The power these paintings reflect through there size is important to painting in the second half of the twentieth century. We read these paintings through the physiological effect that they exhude. This can only be received when standing in front of one of them, yet we know them best through tiny images in books. When was the last time you stood infront of a Pollock?

There is an energy in the use of the large expanse of space that these painters brought to modern art, through the interaction of colours, the shapes or gestures that remain on the picture plane. In this age of instant gratification, perhaps something is being missed here when not standing in front of a real painting. We can learn a lot from looking at developments taking place little over a hundred years ago by Monet. A debt of gratitude that the art historian Jed Pearl in his article, 'After Monet', Modern Painters, Spring 1993. He suggested many artists have followed in the direction of Monet, perhaps indirectly, and with specific interest in the late and large series of paintings entitled 'Water Lilies’. These are now in the Musee de' l'Orangerie, Paris, at MOMA, New York and London's Tate Modern, to name a few.

Claude Monet. Water Lilies. c.1920.

Oil on canvas, triptych, each section 6'6" x 14" (200 x 425 cm).The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund. (Photograph ©1997 The Museum of Modern Art, New York, by Kate Keller/Erik Landsberg)

This is often where there is a concern with the modern artist and his/her choice in subject matter. Good painting doesn’t need subject matter. How important is it that something is from reality or non figurative? The interest for me, lies in what response we receive from the painting, for instance, as a subject matter how interesting are water lilies on the surface of a pond? Is it the way the water lilies are painted that we pick up on or is it the transference of the water lilies into paint onto the surface of the canvas that we some how receive visually? In this way good painting transmits a signal that requires more than just an intellectual response, surely it triggers your visual experience, and that subsequently triggers your emotional response, just like music can.

When visiting the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art as a student, I stood in a large room of Clifford Still paintings, they were the large, black, red, yellow and brown paintings from the late fifties, they opened up the room in terms of colour and space, they jumped back and forth, what Hans Hofmann called the ‘push and pull’ of the picture plane. These paintings came alive in a way that was not just visual, especially those jagged fault lines of Stills; compressed next to each other like the surface of a cliff (no pun intended). It was a defining moment for me; I then went around the museum, looking at the paintings through this understanding of a perceived depth, trying to decipher the paintings through this 'visual experince' which could actually be called 'sensation'. The funny thing was, I was not even fond of Still’s work, but the concept of painting in that way, in that size, worked, it could equally have been Pollock, Rothko or Kline, or any of the others come to think of it..

The painting of Cy Twombly work in a similar way. His paintings are the ultimate in ‘epic’ sized ideas, especially in An Analysis of a Rose as Sentimental Despair a triptych from 1985, Twombly is transmitting something powerful, a subdued act. It echoes what Harold Rosenberg suggested in the 1950's:

At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American after another as an arena in which to act...What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.

Cy Twombly, Untitled panel V of V

(An Analysis of the Rose as Sentimental Despair)

(the colour is more subtle on the original painting)

Few artists seem to communicate in this strange energised frequency that Twombly maintains, yet Joan Mitchell comes close. For these artists abstraction is not just somewhere to explore and experiment with gestures, marks and forms. Nor is it a safe platform for visual communication, good abstraction, occupies an arena that is constantly moving, vibrating with energy and restlessness. It should draw in some other element; an unexpected spontaneous response through marks, a deliberate choice of colour that creates an awkwardness to the painting etc, to ensure that it does'nt fall into an all too easy parody of beauty. A number of works stand out as powerful evocations of this ‘arena’.

The large triptych at the Whitney Museum entitled Clearing by Mitchell, is one of them, with its large echoing black lozenge shapes and mauve ringed areas, and a later one ‘Untitled’ a diptych from 1992, that hovers in the centre of the paintings like the boughs of two trees in a Japanese garden.

Joan Mitchell, Clearing, 1973, oil on canvas, triptych, 9' 2 1/4" x 19' 8”

This painting can be traced back to Monet and his energised responses to the water lilies at his house in Giverny, France, towards the end of his life. Even if Mitchell is unaware of it, the influence is there. Monet’s paintings were shown later in New York after World War II, and bought by MOMA, seemed to have meant more to Abstract Expressionists, than any other artists in Europe at the time, except perhaps the artist Patrick Heron, who followed the modernist cause from Monet through Bonnard and Cezanne to Matisse and Braque, but didn’t expand his paintings on the scale of the American painters, until the sixties and seventies, but I'll be discussing him later.

Where else can we see the influence of Monet?

At the Whitney retrospective exhibition of Mitchell’s work, an essay in the catalogue brings forward the significance of the series of paintings, twenty-one in total painted in 1983–84 called 'La Grande Vallée'. Their is an essay by Whitney curator Yvette Y. Lee devoted to the series. Unfortunately, only three of the paintings are in the show, which makes it impossible to assess the impact of a body of work ideally seen as an environment. These lush, abundant paintings are landscape impressions, predominantly floral in feeling. They clearly echo Monet's 'Water Lilies' and other garden subjects like 'The Japanese Footbridge', and the 'Grande Vallée' cycle is deeply indebted to the Impressionist master, never mind the repeated denials by the catalogue authors.

But lets look at the processes used by Joan Mitchell in her painting:

Her paintings are about the very materiality of paint; slashing strokes, colour over colour and scratchy, tangled lines characterize these early works from the fifties.

Mitchell worked to a distinctive palette and personal vocabulary of marks from beginning to end. Green, blue, orange, black, and white are favoured colors. According to Brenda Richardson's essay for the Whitney Museum Retrospective, her marks include:

• choppy vertical smears, rather like a color test, usually in pairs,

• thin "washes" of pastel hues (lime, flesh, rose, slate blue)

• daubs of impasto, almost always on top of other paint

• slashing strokes, long and stiff, vaguely scimitar-like

• eroding or "melting" once-geometric rectangles, mounds, or blobs and drips

Nearly all her paintings use nearly all her colours and all her marks in some combination; the paintings are almost always all-over mat in finish (glazed bits appear only occasionally). A painting like 'Low Water', 1969, is absolutely classic Mitchell, combining all of the above in hieratic descent.

Joan Mitchell, Ici, 1963

Mitchell first visited Paris in 1948 and was to stay there from 1955 until she died in 1992. During this time she met the Canadian-born French artist Jean-Paul Riopelle; they remained close for the next 25 years, lived together from at least 1960 to 1979. There was a close dialogue between his Surrealist-influenced "action" painting and her own Abstract Expressionist oeuvre. There are also in Mitchell's art the impact of contemporaries like the German abstract painter and theorist E.W. Nay, who developed the theory that "to paint is to form the picture from colour." A similar approach adopted by Patrick Heron at around the same, this is discussed later in this essay. Mitchell lived on the banks of the Seine at Vétheuil from 1967. Paris was only thirty-five miles away; here was the cannon of European modern art, the Courbet and the Impressionists at the Museum D’Orsay and Monet’s ‘Water lilies’ at the Orangerie.

As for contemporary artists of the time, she presumably had the opportunity to consider the work of Europeans of shared sensibility, artists like Mathieu, Soulages, de Staël, Vedova, and even Alechinsky and Jorn of the CoBrA group who would have often exhibited in Paris. The CoBrA artists believed in spontaneous painting, what one writer described as "pure psychic improvisation," this view was shared by Mitchell, who said she never planned her paintings, never thought about them, never did preliminary sketches or laid down any "starter" outlines on the canvas. She insisted she just painted what she felt.

What other influenece are there on her work? You could add Phillip Guston’s early abstractions of the fifties and Sam Francis on a good day, Deep, Orange and Black from 1955, in particular. As well as having strong friendships with Philip Guston, they lived in the same apartment block in New York. It was the work of Sam Francis which Mitchell took most creative influence from. What these artists retain in their paintings is a quality that engages your senses rather than your intellectual powers. They state almost immediately a familiarity in their forms that suggests nature, but it is painting imitating nature, a virtual reality drawn from nature, existing in colour pigment, gestures, the use of space or the resonance of the forms on a surface, what Irwin Edman stated in ‘Arts and the Man’ back in 1928:

A painting is not a design in spots, meant merely to out do a sunset; it is a richer dream of experience meant to outshine the reality

The subject matter could be trees, it could be a wood, could be an old wall or ruin, it could be anything, but it’s paint responding to the artists physical movements and sporadic hand gestures on the surface of the canvas. the paintings success is at the whim of the artists feeling or his sensations. It’s paint in its most dangerous and potent form…

Another artist who took the large scale painting from Monet was Patrick Heron. Consider, the late Heron paintings from the eighties, that he called ‘Garden’ paintings. They retain a freshness and vibrancy still. when looking at these paintings are we meant to perceive these forms squeezed straight out of the tube across the canvas or the blobs of pigment as specific native flowers from Australia, where many of the paintings were made? Or like the Clifford Still paintings do they respond physiologically? Again that feeling of space is present, of a space made from colour. Heron did suggest that the time has come to give up 'to truly sensational painting.’ Here he is not copying nature but evoking it.

Let's look at Heron in more detail:

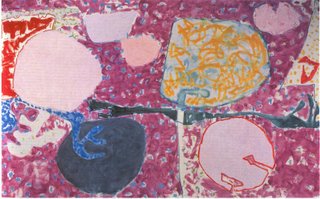

Patrick Heron,Big Purple Painting: July 1983-June 1984

Big Purple Garden Painting: July 1983-June 1984…This painting has similarities to the paintings of Mitchell’s, as a horizontal canvas that echoes Monet’s late paintings. On Heron, Mel Gooding referred to reading 'Big Purple Garden Painting', through the lateral scanning across the canvas:

..a process of continuous apprehension that moves across the surface, from left to right and back again as the eye is enhanced by the flicker of light, and then caught by the space of the experienced world, and the eye seems to glide into an indeterminate distance, potentially infinite.

But as Gooding continued to discuss, there are obvious differences, Monet, being a nineteenth century painter, is interested in the ‘descriptive’ qualities of paint and Heron, being a late twentieth century painter who’s raison d’etre is ‘paint as colour, colour as paint’.

But again we have this interest in the ‘visceral’ qualities of paint, where the transformation from an observed and lived experience like Monet to the more ‘sensed’, in Herons words, to ‘translate sensation into terms of aesthetic emotion’.

What is interesting is considering Heron in the same light as Twombly and Mitchell as a lyrical abstraction painter. I believe we have a series of paintings that emerged in the early eighties from Heron’s Porthmoer studio in St.Ives, Cornwall that will be seen as a highly significant body of work, that should be considered with Twombly and Mitchell's oeuvre.

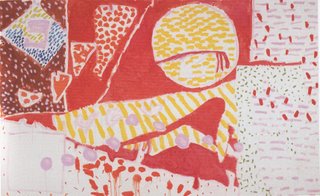

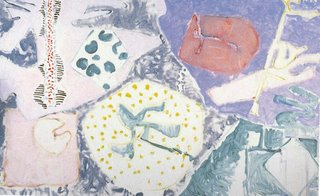

Alongside Big Purple Garden Painting: July 1983-June 1984, there is Red Garden Painting: June 3-5 1985, White Garden Painting: May 25-June 12, and Pale Garden Painting: July-August 1984. To me these are the embodiment of what painting is about, they sit individually as explorations of paint on a surface tracing the artists movements in front of the canvas, transformed to spontaneous actions on its surface. These evocations could refer to a real landscape but this never really emerges, they exist as an alternative landscape transformed through ‘sensation’.

Patrick Heron, Red Garden Painting:June 3-5, 1985

Patrick Heron, Pale Garden Painting, July-August 1984

Joan Mitchell, Cy Twombly and Patrick Heron are still painters that retain a fragility, a concentrated energy in their work, a possibility of what painting can achieve.

To sum up, in 1958, Cy Twombly he wrote in the magazine L'Esperienza Moderna:

'Action must prove from time to time the realisation of life. Act is therefore the primary sensation. In painting act is the formation of the image, the mechanical action of its evolution, the direct or indirect impulse brought to exasperation in this high act which is invention'

Bibliography:

Jed Pearl, After Monet, Modern Painters, Spring, 1993

David Sylvester, Cy Twombly-Theatre of Operations, Modern Painters, Issue 7, 1995

Mel Gooding, Patrick Heron, Phaidon, 1994

Richard Green Galleries, Patrick Heron: The Shape of Colour, Exhibition catalogue, May 2006

Siri Hursvedt, The Mysteries of the Rectangle-Essays on Painting, Princeton Architectural Press, 2005

Alan Gouk, Article: An Evening with Patrick Heron: 1998, State of Art: Notebook

James Elkins, What painting Is, Routledge, 2000

Brenda Richardson, Review: Joan Mitchell exhibition, Whitney Museum, 2002